We Live in Public (Ondi Timoner) – SXSW 2009

I’m sure you’ve heard the term, “one’s own worst enemy.”

The documentary, “We Live In Public,” is an insightful, entertaining, and at times, heartbreaking story of the life of Josh Harris, a recognized Internet visionary from the Silicon Alley set in the ‘90s predicted where the net was going before it happened. This was a decade before people even imagine the worldwide popularity of Facebook and Twitter.

Directed by Ondi Timoner (director of “Dig,” founder of Interloper films, and the only director to win a Sundance grand jury award twice in the festival’s history), “We Live In Public” goes back to the birth of the Internet when this technology was REALLY introduced into the consumer and business channels, and the part Harris played in its innovation (the Internet’s “official” lifetime is going into its 40th year).

The tagline for the film, “the greatest Internet pioneer you’ve never heard of,” is quite appropriate. I may have been one of a handful of people watching the film that was familiar with the part he played in turning the Web business world into an online and offline frat party.

“We Live in Public” gives one a peek into what took place during the beginning years of the Internet, a piece of history of what to do, but especially, what NOT to do. It also follows not only how the Web evolved, both in technology and within business models (or lack thereof), but how this unique individual transformed in the process.

You see, back in the ‘90s, Harris was inventing ways for people to be social on the net in ways they never imagined. But Timoner goes back even further to time when Harris first came to New York in the ‘80s.

He was a visionary even then. Harris was looking ahead while working for a data research company. He knew he could do better, and did so by starting Jupiter Communications, which focused on Internet usage analytics, competing with the likes of the Gartner Group and other market analytic firms.

When people put their money where their mouth is and there’s a payoff, they’re king. Harris was king. People began to pay attention to what he was saying, most of which kept going to the heart of the Internet: that all we do, who we talk to, what we say, what we post, is a part of the public domain for everyone to see. He also knew that this data would be of value to many companies, thus the reason for Jupiter’s success.

That position on the throne enabled him to become one of the hot startup boys. One of the hotshots that got spreads in Silicon Alley magazine, along with new, cool loft space layouts featuring designer office furniture and New York City views. Quite the way to spend VC money…indeed.

Harris didn’t have to go the VC, begging-for-money route (that came later), since Jupiter went public. With some 10 million in IPO money (some report 20 million, others report $80 mill, so who the hell knows) he was living large, throwing big tech parties and launching Pseudo.com in 1993, one of the first Webcasters to emerge.

The film’s footage captures these moments, made possible through Harris’ own camera efforts and that of the filmmaker Timoner, who met him at one of his parties, which replaced geek fests with cool-kid raves, complete with models sitting on the laps of nerds playing Doom. “Get used to it,” Harris proclaims.

And they did.

This was east coast version of the Internet boom, the bookend to what was taking place in San Francisco and Silicon Valley, at the Industry Standard rooftop gatherings, Razorfish parties, and shindigs thrown at Bimbo’s where more booty business then monetary business was taking place. I’m speaking from experience here.

Even though most people at that time used dial-up to access online video, watching a jerky, small screen size at around 300 x 300 pixels, Pseudo.com was a hit. There were music shows for every genre, that were in a way replacing the anti-music video, boring-as-dirt content that MTV was quickly becoming. Young people were running around, expanding their creative juices to create content for his online version of television (what we greatly depend on today, right?). Harris was now not just the king, he was the damn high court.

The king was also spending those millions, but unlike Jupiter, the monetary side of things at Pseudo.com relied solely on advertising. Hard to know how much.

Harris was also showing a different side of himself beyond his obsession with Gilligan’s Island (the show that was essentially, his babysitter growing up). He began to wear a clown costume out in public, and this persona started to come out a lot more often than his staff would have liked.

As the smoke, literally and figuratively, started to clear and VCs no longer felt like shoveling money into a burning fire, reality started to set in. That’s when the bubble popped.

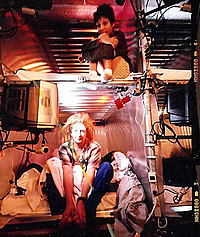

It was right at that time that Harris decided to turn a basement space into a human experiment he called “Quiet.” It was anything but, promoting and encouraging all of the seven deadly sins and more.

|

The next millennium was upon us. A perfect time to for Harris to spend even more money as if “it’s sand through the fingers of time” on setting up video cameras in every crevice of the bunker and have dozens of people file in to have every second of their life—bathroom breaks, showers and sex included—available on each channel for all to see. Endless food, drink, drugs, and guns (yes, there was a gun range) were available for all. Free of charge.

As Wired reported, the “guests” were comprised of, “SoHo painters and poseurs, gallery owners, the Silicon Alley set, media hounds and media whores, Eurotrash, rappers, ravers, and even a smattering of local politicians converged at a huge, defunct textile factory near City Hall.”

Again, the cameras were on the cameras and the people all the way.

This was one of the more compelling moments in the film, where people were expressive and free, as if the Woodstock days were brought back to life, but in the end became leeches, showing the darker side of the human psyche, wanting more and more. And when you mix endless paraphernalia with paranoia, you can only imagine what happened.

It didn’t help that Giuliani was in office, so I’m sure you can guess how he used is moral fist.

At the end of the process, even though the film shows how Harris had an obvious issue with relationships of any kind, he found love. But he couldn’t let go of his addiction to the net and being visible to thousands.

So he created his own personal bunker experiment, weliveinpublic.com, setting up cameras throughout his loft to capture every moment of his relationship with his girlfriend, including cameras not just in the bathroom but in the toilet (probably appealing to all the feces fetish people out there…yuck), along with the conversations he had in the bathroom with his banker. The pressure of losing his money seemed to unravel his ability to cope with himself and in his relationship, and it looked like he was losing his mind as well.

The party was over for everyone, including Silicon Alley. New York Times reported on the magazine’s demise, interviewing its publisher, Jason McCabe Calacanis in October of 2001. ”’The story’s over,’ Mr. Calacanis said. ‘You can’t have a magazine about unemployed people. You can’t have a magazine about people who are taking time off.’ Josh Harris, whose face appeared on the magazine’s cover before his company, Pseudo, closed down, is growing apples in upstate New York. ”

After taking trading the streets of NYC for apple fields, Harris tried to make it once more after the Internet industry healed itself a bit and as social media companies like MySpace.com became the new hot commodity. But by then, no one knew of his vision years earlier that we no longer live in private. No one cared that he was the first to really put people’s lives on the Web, the first to introduce the Web as a social medium.

While Harris’ clown character was pretty creepy, you get the impression Harris was always in character. He recognized and took advantage of the desire the average person has to be a superstar by being in front of any camera, (YouTube.com is further evidence of that), even if they’re humiliated in the process, probably because it was something he desired. Instead of watching the T.V. screen as a boy, as a man, he wanted to be Gilligan and be adored by all. But sitcoms are fleeting.

The timing of the documentary is interesting, considering how social media’s popularity is growing by leaps and bounds while many are concerned with the privacy of those in the playground.

Having cameras document his every move worked out for Harris (his own, others, and the decade Timoner spent gathering thousands of hours film), considering the amount of footage available that made this documentary possible.

The term “monetization” is a popular one at this year’s SXSW as people all discuss how Twitter is eventually going to make money. No one really talked about that in the ‘90s. They were too busy going to IPO after three months to become millionaires on paper. Having sat in a number of VC meetings on Sand Hill Road, I, along with my friend and business partner at the time, were the bitches in room flipping to the end of the business plan looking for the part where the company started making money.

This is a great film for those of us who went through the first Internet boom and lived to talk about it, and for those that didn’t, you’re able experience a part of the Web’s history in only 90 minutes. Highly recommended either way.

In the business world you often see those who are idea people, and then there are those people who take an idea and make it happen over the long term. Make it work to last longer than a flame.

Harris was, is an idea guy. He was crowdsourcing before the term was the twinkle in anyone’s eye. Who’s to say he won’t be back at some point.