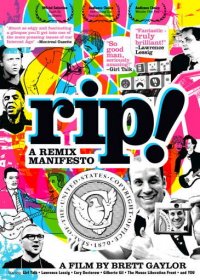

RiP! A Remix Manifesto (Brett Gaylor) – SXSW 2009

Who owns ideas? If an artist creates a truly unique color for a painting, and if another artist thinks, “Cool! I’m going to use that color for my painting,” would the original artist be justified in suing for copyright infringement? Sure, a color could be considered relative, but is it so different from tapping a bass line in one song, “Under Pressure,” for use in another song, “Ice Ice Baby,” by a wanna-be rap pop artist with bad eyebrows?

Web activist and filmmaker Brett Gaylor wants to you think about this issue in his “open source” documentary, “RiP: A Remix Manifesto.”

“Ice Ice Baby” came out in 1990. A few years later the birth of the MP3 sent the music industry into a tailspin. And in 2009, the copyright argument is getting fueled even further by remixes and mashup artists such as the Girl Talk, aka Gregg Gillis, which is at the center of this film.

“Is Girl Talk a paragon of people power or the Pied Piper of piracy?”

Huddled behind his computer his bedroom within his parent’s house, explaining how he pulls samples from 20 or more tracks to create one GL track, one wouldn’t think so. But with computer in hand, Gillis transforms in the nightclub from a mild-mannered biochemist in a lab coat to Girl Talk, a shirtless, sweaty mix master king who leads the kids into a dancing frenzy.

Away from the club, Gillis talks in length about the complications and costs involved in going through the process of legally obtaining the rights to sample music. If he were to abide by all the copyright laws, each song would cost 10s if not 100s of thousands of dollars, not to mention the length of time it would talk…if he were to receive permission from the likes of Wilson Picket or Tears for Fears.

Included in the film is Creative Commons founder, Lawrence Lessig.

According to the Creative Commons website (http://creativecommons.org/), “Creative Commons defines the spectrum of possibilities between full copyright and the public domain. From all rights reserved to no rights reserved. Our licenses help you keep your copyright while allowing certain uses of your work — a “some rights reserved” copyright.

“Creative Commons licenses are not an alternative to copyright. They work alongside copyright, so you can modify your copyright terms to best suit your needs. We’ve collaborated with intellectual property experts all around the world to ensure that our licenses work globally.”

Essentially, this means that if I choose to apply a CC license to this article, I can choose to allow others to redistribute or reuse a part or the entirety of this article providing they notify me of its use and give me credit for writing it. Pretty simple. And no lawyers needed. I set it up ahead of time and let the online tool do the rest.

Lessig, a lawyer, speaker, and director of the Edmond J. Safra Center for Ethics at Harvard (http://www.ethics.harvard.edu/), has worked tirelessly for years within the debate over the legality of copyright laws that exist today. Moreover, he’s excelled at pointing out how today’s laws restrict creativity, and in the case of one woman and mother featured in “RiP…” as an example, have citizens paying thousands of dollars as a result of losing a copyright lawsuit for downloading songs.

(This clip of Lessig is 19 minutes long but very compelling. Two years ago in 2007 he spoke for an audience citing “John Philip Sousa, celestial copyrights and the ‘ASCAP cartel’ in his argument for reviving our creative culture.”)

Brazil’s Minister of Culture Gilberto Gil, has been a proponent for “loosening intellectual property regulations to give more people the freedom to use and republish digital forms of content as a way of encouraging personal expression, culture and political participation,” according to one article on CNN.com.

In Northern Brazil, the dance genre Tecno Brega lives large. Within this music scene, they’ve developed a business model works for their culture. Producers remix music and produce CDs, which they give to street vendors to sell. The street vendors keep the money from those sales, and the producers use the distribution of CDs to promote their sound system parties.

Parties in Tumpinamba, São Paulo, can bring in as many as 5,000 people ready to dance and get nuts. That can also add up to a decent income stream for the producers.

Beto, one producer in Brazil, shows how he took the original meat of “Crazy” by Gnarls Barkley and turned it on its booty. Later in the film, Gilles is in his Girl Talk mode working with Beto’s remix, remixing the remix. Paraphrasing his take on the whole thing, it’s all about “the passing of ideas. Gnarls Barkley creating an idea, the Brazilian created a version that represented their interpretation of that original idea, and then this kid from Pittsburgh cuts it up in his own way to make something new. Artistic growth is recycling ideas.”

Gilles also points out what most music fans and journalists like me know already, that what we hear today is many times an interpretation of what’s been done before. One can’t help but listen to Interpol and think about the influence of Joy Division, a band whose album Closer, has been impacting thousands of bands since it was first released in 1980. That’s just one example. There are many, many more.

The basis of this “RiP” idea is a balance between protecting intellectual property with the rights of people to create.

To rip another quote from a news outlet, “Unless there is a serious updating of copyright law to recognize the changing technological environment, the law becomes an ass,” Lynne Brindley, chief executive of the British Library, told ZDNet UK.

That quote was from 2006. Three years later, are we any further along in this debate?

Gaylor, the director of “RiP,” welcomes one and all to remix this film, providing raw footage, much like raw music tracks, on opensourcemedia.org.